|

Gaugin, Cezanne, Seurat ,Vincent Van Gogh, Gustav Klimt , Lautrec & Henri Rousseau

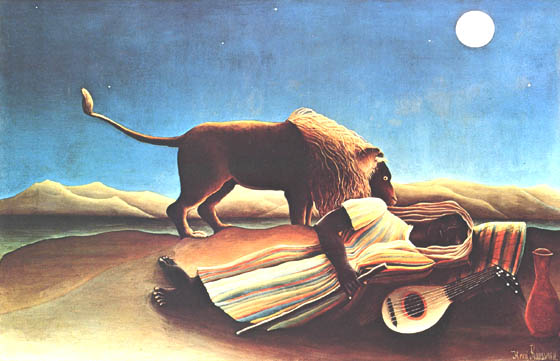

| Boheme by Henri Rousseau |

|

Henri Rousseau's art is fanciful, imaginative, it is the art of the fantastic and is in essence Surreal

and contains elements of Folk Art

-his colouring as bold as Van Gogh as othe-rworldly as Gauguin or Goya

-but it is art which is playful and

accessible yet is in many ways as avant garde as his contemporaries who were concerned with creating a new art for the twentieth

century.

Henri Rousseau has been a difficult artist to pin down during his lifetime and long afterwards and even today. But his work

has not just a deceptively simple or primitive like charm they tease us in their child-like fashion. But they are far more

than that. They are flights of the imagination at times diving into the unconscious sea of seething overgrown and sometimes

frightening jungles composed of archetypes and free associated imagery. Both whimsical and profound at the same time.

One can see how his works in some way influenced later artists from Picasso, Chagall, Georges Braque , Fernand Leger to Diego

Rievera and Frida Khalo etc.

Below are some articles which attempt to explain the enigma that is Henri Rousseau.

From Art Works Images,Exhibitions, Reviews /Henri Rousseau

Artist: Henri Rousseau (1844 - 1910)

Nationality: French

Movement: Post-Impressionism

Media: Painting

Influences:

Biography:

Henri Rousseau spent his life in the working class a toll collector, a clerk, and a soldier. In 1893, he retired on pension

and began painting to occupy his time. Although he was self-taught, his work retained a sophisticated sense of color and unique

composition. In the 1880’s, Rousseau began to exhibit his paintings but was never completely taken seriously by his

critics and colleagues. After his death, his work influenced the progress of the Surrealist movement.

and from WebMuseum Paris/Henri Rousseau

Timeline: Art of the Fantastic

Rousseau, Henri, known as Le Douanier Rousseau (1844-1910). French painter, the most celebrated of naïve artists.

His nickname refers to the job he held with the Paris Customs Office (1871-93), although he never actually rose to the rank

of `Douanier' (Customs Officer). Before this he had served in the army, and he later claimed to have seen service in Mexico,

but this story seems to be a product of his imagination. He took up painting as a hobby and accepted early retirement in 1893

so he could devote himself to art.

His character was extraordinarily ingenuous and he suffered much ridicule (although he sometimes interpreted sarcastic remarks

literally and took them as praise) as well as enduring great poverty. However, his faith in his own abilities never wavered.

He tried to paint in the academic manner of such traditionalist artists as Bouguereau and Gérôme, but it was the innocence

and charm of his work that won him the admiration of the avant-garde: in 1908 Picasso gave a banquet, half serious half burlesque,

in his honor. Rousseau is now best known for his jungle scenes, the first of which is Surprised! (Tropical Storm with a Tiger)

(National Gallery, London, 1891) and the last The Dream (MOMA, New York, 1910). These two paintings are works of great imaginative

power, in which he showed his extraordinary ability to retain the utter freshness of his vision even when working on a large

scale and with loving attention to detail. He claimed such scenes were inspired by his experiences in Mexico, but in fact

his sources were illustrated books and visits to the zoo and botanical gardens in Paris.

His other work ranges from the jaunty humor of The Football Players (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1908) to the mesmeric, eerie

beauty of The Sleeping Gypsy (MOMA, 1897). Rousseau was buried in a pauper's grave, but his greatness began to be widely acknowledged

soon after his death.

Art of the Fantastic

One artist who prefigured the Surrealists' idea of fantasy with his fresh, naïve outlook on the world was the Frenchman, Henri

Rousseau (1844-1910). Like Paul Klee, he defies all labels, and although he has been numbered among the Naïves or Primitives

(two terms for untrained artists), he transcends this grouping. Known as Le Douanier, after a lifelong job in the Parisian

customs office, Rousseau is a perfect example of the kind of artist in whom the Surrealists believed: the untaught genius

whose eye could see much further than that of the trained artist.

Rousseau was an artist from an earlier era: he died in 1910, long before the Surrealist painters championed his art. Pablo

Picasso, half-ironically, brought Rousseau to the attention of the art world with a dinner in his honor in 1908: an attention

to which Rousseau thought himself fully entitled. Although Rousseau's greatest wish was to paint in an academic style, and

he believed that the pictures he painted were absolutely real and convincing, the art world loved his intense stylization,

direct vision, and fantastical images.

Such total confidence in himself as an artist enabled Rousseau to take ordinary book and catalogue illustrations and turn

each one into a piece of genuine art: his jungle paintings, for instance, were not the product of any first-hand experience

and his major source for the exotic plant life that filled these strange canvases was actually the tropical plant house in

Paris.

Despite some glaring disproportions, exaggerations, and banalities, Rousseau's paintings have a mysterious poetry. Boy on

the Rocks (1995-97; 55 x 46 cm (21 3/4 x 18 in)) is both funny and alarming. The rocks seem to be like a series of mountain

peaks and the child effortlessly dwarves them. His wonderfully stripy garments, his peculiar mask of a face, the uncertainty

as to whether he is seated on the peaks or standing above them, all comes across with a sort of dreamlike force. Only a child

can so bestride the world with such ease, and only a childlike artist with a simple, naïve vision can understand this elevation

and make us see it as dauntingly true.

© 16 Jul 2002, Nicolas Pioch

and from ArtChive/Henri Rousseau

Henri Rousseau (1844-1910)in His Time

"A problem persists with regard to the Douanier Rousseau. Admired by artists at the turn of the century (Pablo Picasso, Robert

Delaunay, Wassily Kandinsky, Constantin Brancusi, and others), and defended by the same writers (led by Guillaume Apollinaire

and Blaise Cendrars) who defended them, he is still difficult to fit into what we call modern art. Thus in 1918, after having

cited the precursors of Cubism and modern painting, Amedee Ozenfant and C. E. Jeanneret (who was not yet calling himself Le

Corbusier) stated: "No need to include among [them] the Douanier Rousseau, one of the most charming painters of the period,

for his art was purely traditional."' A similar judgment was handed down by Ribemont Dessaignes, who was active in the Dada

movement:

"The emergence of Rousseau is an isolated fact separate from the day to day development of art; Rousseau's painting is totally

foreign to every contemporary school, whether oldfashioned or avant garde."

And even Philippe Soupault, who was passionately devoted to Rousseau, refused to place his work in historical perspective.

Tristan Tzara, however, equally devoted to the Douanier, was able to analyze his work more acutely and to understand the role

it played in twentieth century art.

"Such an equivocal situation obviously arises out of the singularity of Rousseau's work and the lack of precedents for it.

Also responsible, perhaps, is Rousseau's ambiguous personality, to which we shall return. There persists even today an error

in historical perspective regarding his precise chronological position: we tend to forget that Rousseau was not the contemporary

of his admirers. Born in 1844, he was very little younger than Paul Cezanne, Claude Monet, and Odilon Redon; his contemporaries

were L. 0. Merson, B. Constant, and Fernand Cormon, all born in 1845. His true contemporary in pictorial adventure is Paul

Gauguin, only four years his junior, who like him began as a Sunday painter and became an artist with a "belated vocation."

Neither began painting in his personal style until sometime around 1885. Of course such a parallel cannot be drawn out indefinitely

Gauguin's artistic quest was more calculated, methodical, and rapid than was Rousseau's; however, innumerable relationships

can be discerned between the two bodies of work. It has long been noted that Rousseau was indebted to Gauguin, whose canvases

he had many opportunities to see.

"Notwithstanding the misleading nature of some of his own statements, Rousseau's art cannot be defined by the greater or lesser

degree of clumsiness with which he assimilated academic procedures. He did of course attempt to conquer Albertian perspective

and to give an illusion of it, primarily in his urban landscapes. In the years around 1890, however, was that really the problem?

If traditional perspective and modeling had been rejected, first by Edouard Manet and then by Cezanne, Monet, Georges Seurat,

and Gauguin, it was because they realized that such procedures had reached a dead end. Unlike Rousseau, however, they had

earlier served their apprenticeships; they had, to varying degrees, acquired the needed skills. Rousseau followed them and,

consciously or not, he benefited from the work they had done. In the last years of the century, painters and the more enlightened

critics realized that it was no longer necessary to master Albertian perspective to express themselves. The deed, of course,

preceded the word, and theoretical writings on the subject are few and far between. However, why should Rousseau be excluded

from this great purgative task, one that was not destructive in its effects but, rather, aimed at the elaboration of new languages

to take the place of a dying tradition? As early as the first Jungle of 1891 (Surprise!) and in many of the portraits painted

around 1900 we can discern methods close to those of Gauguin and the Nabis. It is after 1900, however, and principally in

his exotic compositions, that Rousseau evidences his mastery of a formal language that no longer owes anything to traditional

methods. Many critics, even those not fond of Rousseau, have quite rightly evoked Persian, Japanese, or medieval models when

writing of his Jungle pictures. Are those sumptuous vegetal decors, in which the spread of fantastic greenery is punctuated

by marvelous, multicolored flowers, a reminiscence of the so called mille fleurs tapestries of the late Middle Ages that he

might have seen in his youth in Angers, or in Paris at the Musee de Cluny? Perhaps. Such vegetation, at once dense and without

depth, with the thick foliage of the Barbizon school (although without the clever interspersal of vistas), and far removed

from the Impressionists' airy landscapes, may not, however, be particular to Rousseau. A survey of pictorial production around

1900 would in fact reveal many other comparable examples in Gauguin, of course, in late Cezanne, and in the younger generation,

Picasso, Fernand Leger, and Raoul Dufy.

"Around 1890, in and around Paris but most of all in the vicinity of Aix en Provence, Cezanne, had begun to paint skyless,

horizonless clearings in the woods. Monet's earliest Waterlilies, with their profuse, invasive vegetation, were exhibited

in 1900. Although somewhat later, Redon's frescoes at the Abbaye de Fontfroide (1910-11) are in a way the logical extension

of his earlier work. In all these examples and confining ourselves to artists of Rousseau's own generation we find painters

expressing the same desire: to depart from nature to create a pictorial fact, leading them to the limits of the imagination,

abandoning the problems of depth and perspective. Man is excluded, but the profusion, richness, and eternal springtime of

their flora endows them with a pantheistic significance that is far different from the earthbound horizons of the Barbizon

school or the dainty settings for Impressionist outings; this pantheistic feeling is especially powerful in the late Waterlilies

and in Cezanne.

"Outside France, in the work of Gustav Klimt or Augusto Giacometti, for instance, it is possible to find other examples of

flat vegetal decor that invades the entire surface of the painting. Nor should we overlook the achievements of Art Nouveau

in the area of applied arts. Yet must we revive the somewhat tired notion of influence, fix exact dates, and verify opportunities

for actually seeing works or photographs? Those might be useful pursuits were it a question of a particular borrowing, but

is it necessary for a convergence of related phenomena? Rousseau could have seen such and such a work, particularly at the

Salon des Independants where he showed regularly and at which he must have been a sedulous visitor. Did he see the Cezanne

exhibition at Vollard's in 1895; did he frequent Durand Ruel or Bernheim Jeune? For a man like Rousseau, alert to the visual

world, a man whose entire output reveals an intense drive for renewal, the glimpse of a few works, the decor of a facade or

designed paper, some engraving, any isolated impulse, could have sufficed to capture his attention and inspire a meditation,

conscious or unconscious, on the problems of his craft. There are more than twenty Jungle paintings, almost all of which are

large in scale. Even taking into account the uncertainties of their chronology, most of them can still be dated post 1904;

their production, interspersed with the execution of other, often large scale, works, was thus something around four per year.

Whether out of a process of slow ripening or sudden intuition, Rousseau found and at once mastered a landscape formula that

enabled him fully to express himself and at the same time to resolve or circumvent technical problems that had hitherto held

him back.

"The profusion of tropical vegetation also reflects another of Rousseau's desires. This impecunious suburbanite, aware that

he had led an unadventurous life, was through the evocation of the "incredible floridas" of Arthur Rimbaud's visions to satisfy

his own need for dream, for escape the same escape Rimbaud and Gauguin had sought in flight and revolt; that Pierre Loti (whose

portrait Rousseau painted c. 1891) was to realize in the conformist career of naval officer and celebrated novelist; that

Redon, Gustave Moreau, Fantin Latour, and Stephane Mallarme would find by taking refuge in their inner worlds, Monet beside

his pond, Cezanne opposite his mountain.

...

"Although our image of the Douanier Rousseau is linked to his Jungles now popularized even in song his repertoire of subjects

is much richer. At the end of the nineteenth century, when nearly every artist, whether academic or innovative, confined himself

to a few subjects, Rousseau's work covered a broad range: still life, genre paintings, individual or group portraits, historical

scenes. He even provided a strange collection of farm and domestic animals. Perhaps this should be regarded as another form

of escape for a city dweller. In Rousseau's day there were still many farms in the Parisian suburbs. The painter showed an

equal originality in the sphere of portrait landscapes, which he claimed to have invented: as in The Muse Inspiring the Poet,

his portrait of Apollinaire and Marie Laurencin, flowers are detailed with a botanical care that is almost unique at this

period.

"As for the city landscape, for Rousseau it forms a kind of counterpoint to the exotic landscape. After Charles Meryon and

Gustave Caillebotte and at the same time as Camille Pissarro and Maximilien Luce, he was imbuing banal modern urban vistas

with grace and poetry. He was also fond of colorless suburban neighborhoods, and he unhesitatingly used determinedly modern

motifs in his pictures, for example factory chimneys in Chair Factory (c. 1897). In this he had few predecessors other than

Seurat and Cezanne, (in the Views of L'Estaque).

But whereas Cezanne, evidenced little taste for modernism and is

said to have complained about the installation of streetlights and the "biped invasion" at L'Estaque, Seurat on several occasions

used streetlights to give rhythm to his compositions, investigated artificial lighting, and painted The Eiffel Tower, the

first and for a long time the only painter to dare do so. All these motifs, save for the artificial light, were to be taken

up by Rousseau as well. And if Robert Delaunay chose the Eiffel Tower (The City of Paris), still an object of loathing in

some art circles, as his symbol of modernity and one of the bases for his experiments with form, he owed the idea in part

to Rousseau (Myself Portrait Landscape, 1890), of whom he was a great admirer. There are other examples of Rousseau's consistent

taste for subjects that represented technological innovations, the most spectacular being his many paintings of airplanes

and dirigibles, which he set in the Parisian sky (The Quay of Ivry and The Fisherman and the Biplane); here, too, he was followed

by Robert Delaunay, as well as by La Fresnaye.

"There is a fundamental difference between the significations of the two categories of landscape. The Jungles almost always

have the look of impenetrable grills, or screens, before which the conflict unrolls; whereas the pictures of city or suburb

are open landscapes through which peaceful strollers promenade. Rousseau's landscapes are filled to an obsessive degree with

means of communication: streets, country paths, bridges, vehicles, and, more original, balloons and airplanes. Rivers, nearly

absent from the tropical landscapes, appear in almost all the suburban views of Paris. When he creates populated scenes he

reconciles social classes (A Hundred Years of Independence, 1892, La Carmag nole, 1898) or States (Representative of Foreign

Powers arriving to Hail the Republic as a Sign of Peace).

The repeated presence of two of Frederic Auguste Bartholdi's

colossal sculptures, the Statue of Liberty and the Lion of Belfort, is surely not without significance. Both statues had a

precise political meaning: Liberty, in New York harbor, stressing the ideal community between the two Republics, France and

America, at a time when most countries were living under monarchies, and the Lion, located in Paris, recalling the defense

of Belfort, an heroic episode from the 1870 Franco Prussian War. Similarly, there can be nothing fortuitous about the continual

recurrence of the three national colors (and sometimes only the two, blue and red, of the City of Paris).

"Contrary to popular belief, Rousseau was hardly uneducated; secondary studies, even when uncompleted, were in his day the

accomplishments of the minority. He ended his formal education filled with the zeal of a man believing in the virtues of science

and progress. He filled his teaching post at the Philotechnic Association in the same spirit; we also know that he was interested

in the political life of his quartier and that he was a Freemason. His two extant plays (the manuscript of the third appears

to be lost) are written in an easy style.

In short, Rousseau's level of education was higher than average for petty

civil servants at the time and very much on a par with that of other artists, J. F. Millet for example. Can we go further?

The liberated fantasy of certain of his compositions, his unique expression of dream and the irrational, the pantheism of

his Jungles, all recall trends of thought prevalent in his day.

There is no question of turning Rousseau into a reader

of Lautreamont, a disciple of Sar Peladan or Eliphas Levy, or into a frequenter of Symbolist or Decadent cenacles. Did he

even know the names of Mallarme or Huysmans? We do not know, but on the other hand, why reject any coincidence between Rousseau's

outlook and that of many other artists and writers (some of whom acted as critics at the Salons) who were opening windows

to air out the stuffy prosiness of the period? He too was "tired of this antique world."

"Once again we must face the problem of Rousseau's unique personality. Was he the simple naif intoxicated by his belated success

and the compliments of his admirers described for us by some of his earliest biographers? There can be no doubt that his behavior

often evidenced a kind of naivete, not to say obliviousness for example, in the rash acts (the adjective is a mild one) that

led him into the courtroom.

However, on that occasion his very "naivete" served him well in the outcome of his trial,

and we may wonder whether he was not wisely playing the fool. In the end, our overriding impression is of a certain finesse,

of a sometimes clumsy trickiness, but also of a stubborn courage in pursuing and "improving" his work, and, thus, of an indifference

to anything that did not touch upon that work.

His letters, which constitute the most serious testimony to his state

of mind, are explicit in this regard. Andre Malraux noted in Rousseau "the type of childlike but cunning power that poets

often have".

- From "Rousseau in His Time", by Michel Hoog, in "Henri Rousseau"

|

|

| Vincent VanGogh |

|

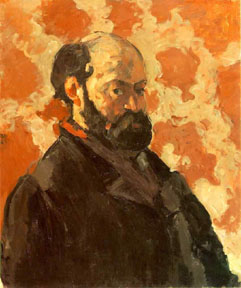

| Paul Cezanne: Self-Portrait |

|

| Paul Cezanne: Mount Victore |

|

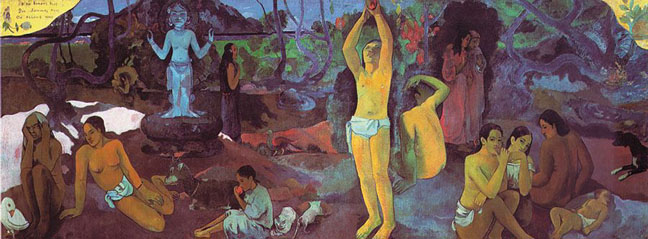

| Paul Gaugin : Where... |

|

| Paul Gaugin: Portrait of Van Gogh |

|

| Vincent VanGogh: Threatening Skies |

|

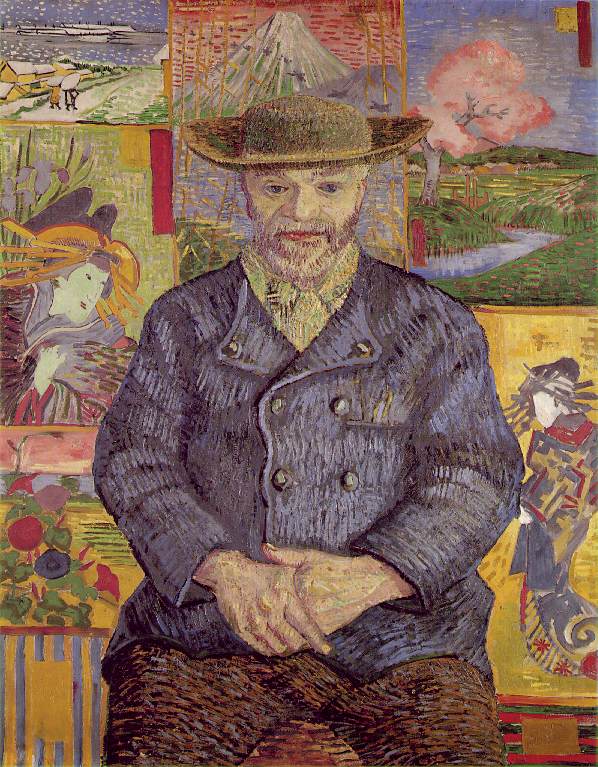

| Vincent VanGogh: Tanguy |

|

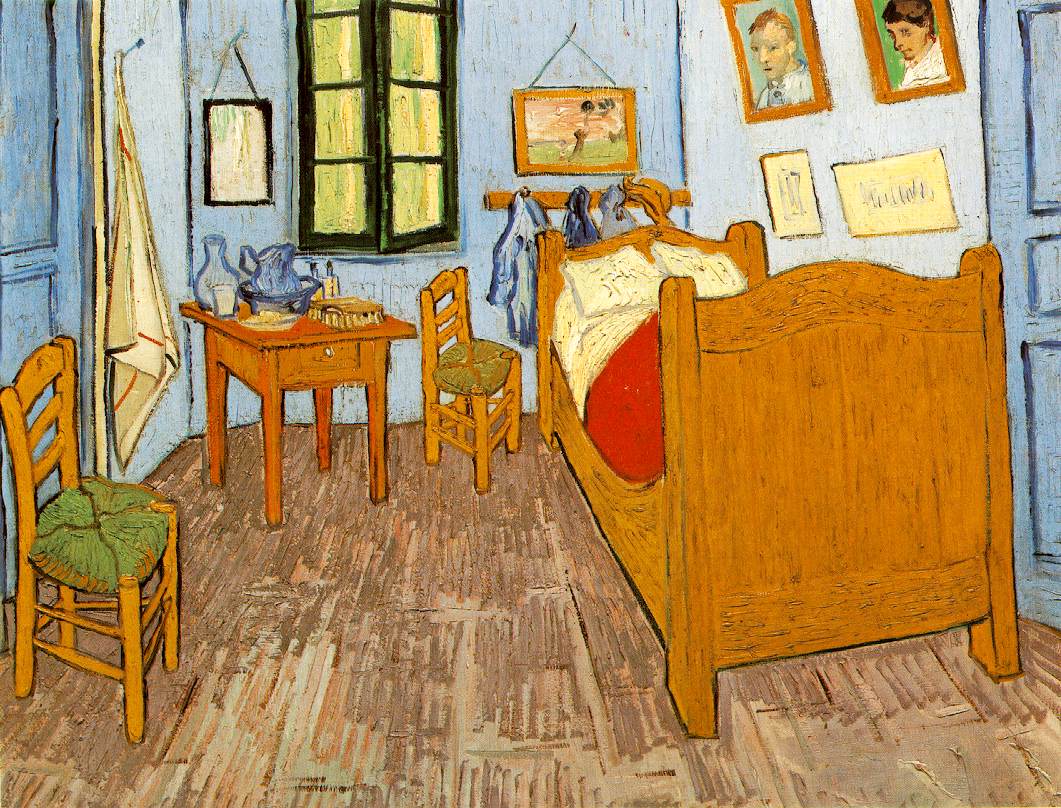

| Vincent VanGogh: Room At Arles |

|

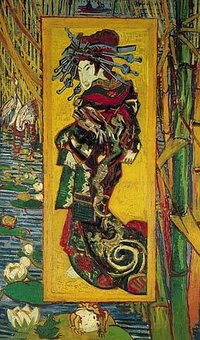

| Vincent VanGogh: Courtisane Japanese style |

|

VAN GOGH"

PAINTING "STARRY NIGHT " BY POST-IMPRESSIONIST

VINCENT VAN GOGH(1853-1890)

Posted by Hello

SCULPTURE BY JOHN COLL "VAN GOGH

ON THE ROAD"

Posted by Hello

SELF-PORTRAIT VINCENT VAN GOGH

(1853-1890)

POST-IMPRESSIOIST

Posted by Hello

PAINTING BY POST-IMPRESSIOIST

VINCENT VANGOGH( 1853-1890) " BRIDGE IN THE RAIN" ( AFTER THE JAPANESE STYLE)

Posted by Hello

PAINTING " WHEATFIELD WITH CROWS"

BY VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

Above are paintings of one of my favourite artist Vincent Van Gogh

whose works are filled with such passion and an exuberance of bold colouring which was a departure from the pastel pallette

of the French impressionists painters who preceded him.

See website: Vincent Van Gogh Art Gallery

WWW.vangoghgallery.com

& John Coll website

Irish artist b. 1956

( THE LIGHT BEHIND THE WRITTEN WORD)

www.kennys.ie/Exhibitions/1998/coll/exhibits

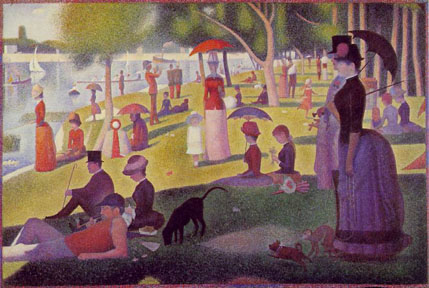

| Georges Seurat: Jatte |

|

from : ArtMovements/ Post-Impressionism

POST IMPRESSIONISM

KEY DATES: 1880-1920

Post-Impressionism in Western painting, movement in France that represented both an extension of Impressionism and a rejection

of that style's inherent limitations. The term Post-Impressionism was coined by the English art critic Roger Fry for the work

of such late 19th-century painters as Paul Cézanne, Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec,

and others. All of these painters except van Gogh were French, and most of them began as Impressionists; each of them abandoned

the style, however, to form his own highly personal art. Impressionism was based, in its strictest sense, on the objective

recording of nature in terms of the fugitive effects of colour and light. The Post-Impressionists rejected this limited aim

in favour of more ambitious expression, admitting their debt, however, to the pure, brilliant colours of Impressionism, its

freedom from traditional subject matter, and its technique of defining form with short brushstrokes of broken colour. The

work of these painters formed a basis for several contemporary trends and for early 20th-century modernism.

The Post-Impressionists often exhibited together, but, unlike the Impressionists, who began as a close-knit, convivial group,

they painted mainly alone. Cézanne painted in isolation at Aix-en-Provence in southern France; his solitude was matched by

that of Paul Gauguin, who in 1891 took up residence in Tahiti, and of van Gogh, who painted in the countryside at Arles. Both

Gauguin and van Gogh rejected the indifferent objectivity of Impressionism in favour of a more personal, spiritual expression.

After exhibiting with the Impressionists in 1886, Gauguin renounced “the abominable error of naturalism.” With

the young painter Émile Bernard, Gauguin sought a simpler truth and purer aesthetic in art; turning away from the sophisticated,

urban art world of Paris, he instead looked for inspiration in rural communities with more traditional values. Copying the

pure, flat colour, heavy outline, and decorative quality of medieval stained glass and manuscript illumination, the two artists

explored the expressive potential of pure colour and line, Gauguin especially using exotic and sensuous colour harmonies to

create poetic images of the Tahitians among whom he would eventually live. Arriving in Paris in 1886, the Dutch painter van

Gogh quickly adapted Impressionist techniques and colour to express his acutely felt emotions. He transformed the contrasting

short brushstrokes of Impressionism into curving, vibrant lines of colour, exaggerated even beyond Impressionist brilliance,

that convey his emotionally charged and ecstatic responses to the natural landscape.

In general, Post-Impressionism led away from a naturalistic approach and toward the two major movements of early 20th-century

art that superseded it: Cubism and Fauvism, which sought to evoke emotion through colour and line.

and from:- From Mark Harden's Artchive & The Bulfinch Guide to Art History

Post impressionism

A term first used by Roger Fry and adopted by Clive Bell to describe modern art since Impressionism. The 1910 and 1912 exhibitions

of French art organized by them were confusingly entitled 'Manet and the Post-Impressionists', although they included the

work of Matisse, Picasso and Braque. The term is now taken to mean those artists who followed the Impressionists and to some

extent rejected their ideas. They include van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne, Seurat, Signac and Toulouse-Lautrec. Many were involved

with the Societe des Artistes Independants established in Paris in 1884. Generally, they considered Impressionism too casual

or too naturalistic, and sought a means of exploring emotion in paint.

And from:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art/ Post-Impressionism

Breaking free of the naturalism of Impressionism in the late 1880s, a group of young painters sought independent artistic

styles for expressing emotions rather than simply optical impressions, concentrating on themes of deeper symbolism. Through

the use of simplified colors and definitive forms, their art was characterized by a renewed aesthetic sense as well as abstract

tendencies. Among the nascent generation of artists responding to Impressionism, Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Georges Seurat

(1859–1891), Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), and the eldest of the group, Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), followed

diverse stylistic paths in search of authentic intellectual and artistic achievements. These artists, often working independently,

are today called Post-Impressionists. Although they did not view themselves as part of a collective movement at the time,

Roger Fry (1866–1934), critic and artist, broadly categorized them as "Post-Impressionists," a term that he coined in

his seminal exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists installed at the Grafton Galleries in London in 1910.

In the 1880s, Georges Seurat was at the forefront of the challenges to Impressionism with his unique analyses based on then-current

notions of optical and color theories. Seurat believed that by placing tiny dabs of pure colors adjacent to one another, a

viewer's eye compensated for the visual disparity between the two by "mixing" the primaries to model a composite hue. The

Study for "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte" (51.112.6) embodies Seurat's experimental style, which was dubbed Neo-Impressionism.

This painting, the last sketch for the final picture that debuted in 1886 at the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition

(today in the Art Institute of Chicago), depicts a landscape scene peopled with figures at leisure, a familiar subject of

the Impressionists. But Seurat's updated style invigorates the otherwise conventional subject with a virtuoso application

of color and pigment. In Circus Sideshow (61.101.17), he uses this technique to paint a rare nighttime scene illuminated by

artificial light. The young circle of Neo-Impressionists around Seurat included Paul Signac (1863–1935), Maximilien

Luce (1858–1941), and Henri-Edmond Cross (1856–1910).

The art of Paul Gauguin developed out of similar Impressionist foundations, but he too dispensed with Impressionistic handling

of pigment and imagery in exchange for an approach characterized by solid patches of color and clearly defined forms, which

he used to depict exotic themes and images of private and religious symbolism. Gauguin's peripatetic disposition took him

to Brittany, Provence, Martinique, and Panama, finally settling him in remote Polynesia, at first Tahiti then the Marquesas

Islands. Hoping to escape the aggravations of the industrialized European world and constantly searching for an untouched

land of simplicity and beauty, Gauguin looked toward remote destinations where he could live easily and paint the purity of

the country and its inhabitants. In Tahiti, he made some of the most insightful and expressive pictures of his career. Ia

Orana Maria (Hail Mary) (51.112.2) resonates with striking imagery and Polynesian iconography, used unconventionally with

several well-known Christian themes, including the Adoration of the Magi and the Annunciation. He described this picture in

a letter to a dealer friend in Paris: "An angel with yellow wings points out Mary and Jesus, both Tahitians, to two Tahitian

women, nudes wrapped in pareus, a sort of cotton cloth printed with flowers that can be draped as one likes from the waist"

(letter to Daniel de Monfreid, March 11, 1892).

In Two Tahitian Women (49.58.1) and Still Life with Teapot and Fruit (1997.391.2), Gauguin employs simplified colors and solid

forms as he builds flat objects that lack traditional notions of perspective, particularly apparent in the still-life arrangement

atop a white tablecloth pushed directly into the foreground of the picture plane.

Striving toward comparable emotional intensities as Gauguin, and even working briefly with him in Arles in the south of France

in 1888, Vincent van Gogh searched with equal determination to create personal expression in his art. Van Gogh's early pictures

are coarsely rendered images of Dutch peasant life depicted with rugged brushstrokes and dark, earthy tones. Peasant Woman

Cooking by a Fireplace (1984.393) shows his fascination with the working class, portrayed here in a crude style of thickly

applied dark pigments. Similarly, the Road in Etten (1975.1.774) takes the theme outdoors, with laborers working in the Dutch

landscape. Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (67.187.70a) is reminiscent of the rapidly applied divisionist strokes of the Neo-Impressionists,

particularly Signac, with whom Van Gogh became friends in Paris, while the image on its reverse, The Potato Peeler (67.187.70b),

recalls his dark style of the early 1880s. This unique object encapsulates the artist's stylistic experimentations.

Working in Arles, Van Gogh completed a series of paintings that exemplify the artistic independence and proto-Expressionist

technique that he developed by the late 1880s, which would later strongly influence Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and his

circle of Fauvist painters, as well as the German Expressionists. L'Arlésienne (51.112.3) and La Berceuse (1996.435) feature

Van Gogh's style of rapidly applied, thick, bright colors with dark, definitive outlines. After his voluntary commitment to

an asylum in Saint-Rémy in 1889, he painted several pictures with extraordinarily poignant undertones, agitated lines, brilliant

colors, and distorted perspective, which include, among others, A Corridor in the Asylum (48.190.2). Paying homage to Jean-François

Millet, whom Van Gogh had long admired as evident in his very early pictures of peasants, he celebrates the Barbizon artist's

legacy with First Steps, after Millet (64.165.2).

Through their radically independent styles and dedication to pursuing unique means of artistic expression, the Post-Impressionists

dramatically influenced generations of artists, including the Nabis, especially Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) and Édouard

Vuillard (1868–1940), the German Expressionists, the Fauvists, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque (1882–1963), and

American modernists such as Marsden Hartley (1877–1943) and John Marin (1870–1953).

James Voorhies

Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

and :

ArtLex on Post-Impresssionism

EyeconArt/Post-Impressionism

Art General Links:

Virtual Museum Of Art

ARTCYCLOPEDIA

Robin Urton Eyecon Art

PAINTING "MUSIC" BY GUSTAV KLIMT

(1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING "MUSIC" BY GUSTAV KLIMT

(1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING BY GUSTAV KLIMT (1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING BY GUSTAV KLIMT (1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING "PALLAS ATHENA" BY GUSTAV

KLIMT (1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING "PALLAS ATHENA" BY GUSTAV

KLIMT (1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING BY GUSTAV KLIMT (1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING BY GUSTAV KLIMT (1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

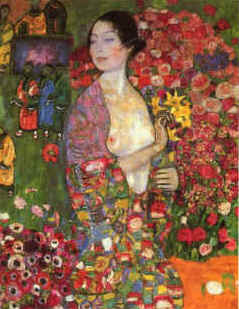

PAINTING " THE DANCER " BY GUSTAV

KLIMT (1862-1918 )

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING " THE DANCER " BY GUSTAV

KLIMT (1862-1918 )

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING "THE PEAR TREE" BY GUSTAV

KLIMT (1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING "THE PEAR TREE" BY GUSTAV

KLIMT (1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

PAINTING " DEATH & LIFE

" BY GUSTAV KLIMT (1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

Above are examples of the ornate & lush & sensuous works of art by the Austrian Gustav Klimt ( 1862-1918)

PAINTING " DEATH & LIFE

" BY GUSTAV KLIMT (1862-1918)

Posted by Picasa

Above are examples of the ornate & lush & sensuous works of art by the Austrian Gustav Klimt ( 1862-1918)

Here are some brief notes about Klimt gleaned from the net.

"Gustav Klimt was born as the son of a gold and silver engraver in a suburb of Vienna. He had a formal art training at the

Vienna School of Decorative Arts.

In 1897 Gustav Klimt founded with other artists the Vienna Secession ( the Nouveau Art Movement) and became its first president.

By that time Klimt had developed his own and characteristic style, which should became the trademark of the movement. Like

impressionism, art nouveau was an International revolt against the traditional academic art style.

Gustav Klimt's style is highly ornamental. The Art Nouveau movement favored organic lines and contours. Klimt used a lot of

gold and silver colors in his art work

Klimt's works of art were a scandal at his time because of the display of nudity and the subtle sexuality and eroticism. His

best know painting The Kiss, was first exhibited in 1908.

From 1900 to 1903 Gustav Klimt worked on commissions by the Vienna University for a series of ceiling murals. For his mural

works Klimt used a wide variety of media - metal, glass and ceramics.

In 1905 Gustav Klimt left the Vienna Secession ...He went into design works for fashion and jewelry. His understanding of

art as something that should not be confined to art academies, studios and canvases ... The very idea itself was again revitalized

with the Pop Art Movement in the sixties and seventies. "

from website

/www.artelino.com/articles/gustav_klimt

And From "Symbolism", a Taschen art book by Michael Gibson.

at Mark Harden's Artchive

www.artchive.com

" Far from being acknowledged as the representative artist of his age, Klimt was the target of violent criticism; his work

was sometimes displayed behind a screen to avoid corrupting the sensibilities of the young. His work is deceptive. Today we

see in it the Byzantine luxuriance of form, the vivid juxtaposition of colors derived from the Austrian rococo - aspects so

markedly different from the clinical abruptness of Egon Schiele. But we see it with expectations generated by epochs of which

his own age was ignorant.

For the sumptuous surface of Klimt's work is by no means carefree. Its decorative tracery expresses a constant tension between

ecstasy and terror, life and death. Even the portraits, with their timeless aspect, may be perceived as defying fate. "

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|